#7 Happy Hour

Plus: The Cazalet Chronicle, why misery is mandatory and being FedExed back to Watford

Since my last newsletter, the planet has been consumed by two Brit-centric cultural phenomena: Oasis-mania and Britishcore. I say planet/consumed: the latter will be familiar to those on TikTok or who read newspaper articles about things that happen on TikTok. Essentially, it is (was?) an online trend that sees people celebrate mundane aspects of British life (I’d argue that the majority of British culture is celebrating the mundane aspects of British life, but anyway). As for Oasis-mania, I think it’s fair to say that it did genuinely consume at least some parts of the planet for a couple of weeks.

As someone who has never consciously known a pre-Oasis Britain, I fully bought into the hysteria: their music is woven so tightly into my childhood memories that I will never be able to have an objective view of the band. For me, Oasis simply are. That said, I have belatedly realised how many aspects of their reception have passed into British cultural trope. For example, their lack of stateside success meant I was under the impression that it was a British rock band’s fate to be largely ignored by Americans (although the US coverage of their reunion - including this bloody awful SNL sketch - suggests that was slightly exaggerated). As I wrote in this Guardian article, I was taken aback to discover as a teenager that they were critically derided in many quarters, and I do feel their treatment is a brilliant example of how blighted the UK is by tall poppy syndrome: anything that is popular and (almost) universally beloved - and whose makers are not chronically self-deprecating - is ripe for a backlash.

Yet Oasis’s return actually set me off on a different nostalgia trip. It concerned another band that soundtracked my childhood and who were - 20 years ago at least - far bigger than Oasis. In 1994, Definitely Maybe was the 21st best-selling album of the year. Carry On Up The Charts - the first compilation from The Beautiful South - was the second.

Even when I was very young, I could tell there was something deeply cringeworthy about The Beautiful South, the band formed by Paul Heaton (whose new solo album is currently engaged in a chart battle with Charli XCX’s Brat remix; I try to avoid cultural relevance with this newsletter but today I have failed) and Dave Hemingway in 1988. It was partly the music (a jaunty, vaguely soulful sound that kind of falls under the banner of “sophisti-pop”, the label applied to knowingly pop-minded British bands like Prefab Sprout and The Style Council in the 1980s), but mainly the words. They were so unlike normal lyrics; so idiosyncratic, specific and un-mired in the typical swirl of vague imagery and cod-profundity that does at least tend to keep eye-watering embarrassment at bay. They also felt very “mature,” both in a sex way and a mumsy, dadsy way, which compounded the uncoolness of it all.

I still loved them though: they may have been cringeworthy but they were also relentlessly funny - I’ll always put up with the former in exchange for the latter. Their output is remorselessly wry - starting with the mordant glare of that name (they’re northerners) - in a way that I think of as being very British, which is why I was surprised to learn from a recent interview that Heaton (who, by the way, is a rare example of a musician who supports critics: I was one of the beneficiaries of his largesse when he gave the late Q Magazine a load of money to split between its writers and employees; let’s just say I was mightily relieved to recall that I’d given his album a good review in the Guardian a few years before) - decamps to pubs in Holland or Germany to write his more maudlin lyrics because Britain isn’t bleak enough (Britain… not bleak… enough?!).

Yet my favourite example of Heaton’s droll but cosy cynicism is Happy Hour - not a song by The Beautiful South, but a no. 3 hit in 1986 for his and Hemingway’s previous band The Housemartins, whose line-up featured a young Norman Cook (AKA Fatboy Slim - who performed the song alongside Heaton at this year’s Glastonbury, reuniting the pair on stage for the first time in 36 years!) and who were a bit more on-the-nose and tongue-in-cheek with their anti-southern sentiment (London 0 Hull 4 was the name of their debut album).

The song is a sardonic celebration of heart-sinkingly misogynistic post-work bants, where wannabe yuppies “open all their wallets” and “close all their minds” and claim “women grow on trees”, atop some shuffly, jangly indie. Heaton sounds extremely Morrissey-esque (imagine if The Smiths hadn’t taken themselves quite so seriously) while the video has the band coming over like four corporate Ricks from The Young Ones. According to the YouTube description, the choreography - and what choreography - is a nod to Monty Python’s Ministry of Silly Walks (I would have said there are traces of Mr Bean in there too but this predates his first TV appearance by four years).

Happy Hour - which is caked for me not in nostalgia but anemoia; wistfulness for a time and place one has never known (pubs in the 1980s) - is technically a work of satire (unhappy hour, more like!), but it’s satire of a peculiarly British kind. There’s a feeling of resignation - it is far from a call to arms against sad, lazily sexist show-offs - that folds into the mild pessimism that blankets our entire culture (and which we like). Then what the song does - also typical - is extract joy from that inevitable disappointment, combining it with the fast, fidgety percussion and pealing riffs (and silly dancing) to produce something oddly cheering and comforting - like a blast of sour warmth from inside a pub on a cold night. In this sense, Happy Hour anticipates another TV comedy - by a whole 15 years: The Office, which although colder, did squeeze glee from this country’s grey, idiotic shitness.

Another thing: Heaton has said that people went wild for Happy Hour when it was played in pubs, missing the irony. But that embrace doesn’t necessarily rely on misinterpretation: the song is essentially banter about banter, feeding into a never-ending loop of unseriousness that in some ways is the delight and some ways the shame (see: Boris Johnson) of this country.

When researching this song, I read that a previous version was called French England. “I was working in a ledger office in Surrey, and as a northerner I saw that whole area as part of France,” said Heaton. “So the original first line was ‘French England, what a good place to be’.” Maybe I’m too young/too not-northern, but I have never encountered this idea before. Made me laugh though.

NOTES AND RECS

I am in literary mourning. Over the past month I have mainlined The Cazalet Chronicle, Elizabeth Jane Howard’s five-novel series that follows a wealthy middle-class family from the late 1930s to the late 1950s, and now it’s all over I’m desperately missing Polly and Villy and Rupe and Archie and Clary and Neville and the whole clan (not Edward). Howard captures this period - within a very specific class, location and sensibility - so evocatively and with so much humour that I am genuinely devastated that I won’t be able to read these books for the first time ever again. Told via the frequently swapped perspectives of the extended Cazalet clan, their staff and friends, the novels (the first of which was published in 1990) capture this tumultuous period of British history strictly from the domestic and familial sphere - put it this way: childbirth is a bigger source of tension than the Blitz. Howard manages to surreptitiously weave an incredible amount of social history into what are ostensibly such people-y books (they are also semi-autobiographical), something that makes them as bingeable as a reality show and similarly packed with uncomfortable depictions of human beings as they actually are. I am also in love with the vernacular: a tedious man is a “howling bore”; when kids say funny things, they are “killing”. I have mentioned disgusting food as a cornerstone of so much British culture before and it is here in spades. During wartime bread is invariably spongy and grey, tea is grey and margarine is bright yellow. As per Oasis, the only real pleasures are cigarettes and alcohol.

I recently wrote about The Franchise, the new HBO superhero movie pastiche dreamed up by Armando Iannucci and Sam Mendes, but in practice helmed by comedy writer Jon Brown. When I was reading about Brown - who has worked on Succession and The Thick Of It - I came across this interview he did in 2017, in which he talks about his adaptation of an Israeli comedy called Loaded, which follows four men who become overnight millionaires after selling their company. While the original series was “aspirational”, Brown says he had to make his version more “tainted” as British audiences can’t stomach the combination of wealth and happiness. “We like to see people whose lives are difficult and miserable and real.” I think that’s totally true. But why?!

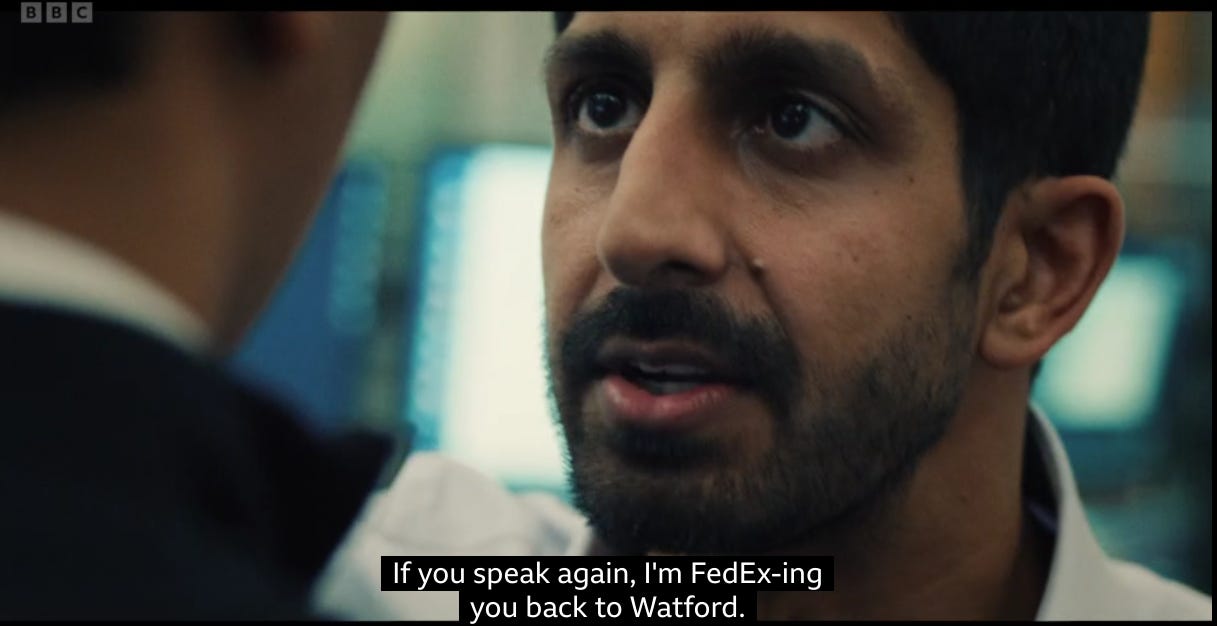

On the subject of The Franchise, I am getting pretty confused about the national provenance of some TV shows. Such as the INCREDIBLE Industry - whose third series is a whole new level of deliciously insidery, profanity-laced tension. Like The Franchise, Industry is written by Brits, acted largely by Brits and set in Britain, yet because both are funded by HBO, they air in the US weeks before they do here and seem to be considered in some way American (you could also put Succession - HBO again - in this bracket in light of its British creators and writers, and many British cast members). Does this make them actual transatlantic programmes? I can’t decide. But I ask you: how is an American person supposed to get the full effect of this subtly devastating line?